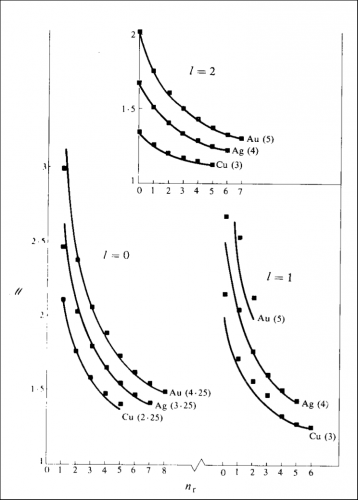

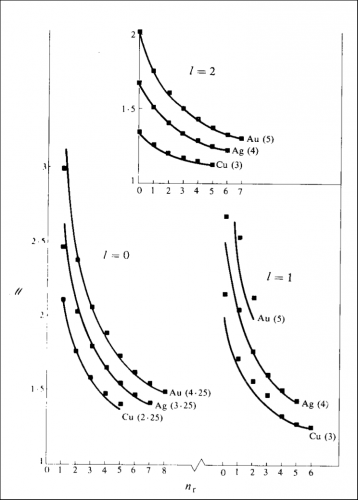

In a previous post, I questioned whether gold showed relativistic effects in its valence electrons. I also mentioned a paper of mine that proposes that the wave functions of the heavier elements do not correspond exactly to the excited states of hydrogen, but rather are composite functions, some of which have reduced numbers of nodes, and I said that I would provide a figure from the paper once I sorted out the permission issue. That is now sorted, and the following figure comes from my paper.

The full paper can be found at

http://www.publish.csiro.au/nid/78/paper/PH870329.htm and I thank CSIRO for the permission to republish the figure. The lines show the theoretical function, the numbers in brackets are explained in the paper and the squares show the "screening constant" required to get the observed energies. The horizontal axis shows the number of radial nodes, the vertical axis, the "screening constant".

The contents of that paper are incompatible with what we use in quantum chemistry because the wave functions do not correspond to the excited states of hydrogen. The theoretical function is obtained by assuming a composite wave in which the quantal system is subdivisible provided discrete quanta of action are associated with any component. The periodic time may involve four "revolutions" to generate the quantum (which is why you see quantum numbers with the quarter quantum). What you may note is that for

ℓ = 1, gold is not particularly impressive (and there was a shortage of clear data) but for

ℓ = 0 and

ℓ = 2 the agreement is not too bad at all, and not particularly worse than that for copper.

So, what does this mean? At the time, the relationships were simply put there as propositions, and I did not try to explain their origin. There were two reasons for this. The first was that I thought it better to simply provide the observations and not clutter it up with theory that many would find unacceptable. It is not desirable to make too many uncomfortable points in one paper. I did not even mention "composite waves" clearly. Why not? Because I felt that was against the state vector formalism, and I did not wish to have arguments on that. (That view may not be correct, because you can have "Schrödinger cat states",

e.g. as described by Haroche, 2013

, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52: 10159 -10178). However, the second reason was perhaps more important. I was developing my own interpretation of quantum mechanics, and I was not there yet.

Anyway, I have got about as far as I think is necessary to start thinking about trying to convince others, and yes, it is an alternative. For the motion of a single particle I agree the Schrödinger equation applies (but for ensembles, while a wave equation applies, it is a variation as seen in the graph above.) I also agree the wave function is of the form

ψ =

A exp(2

πiS/h)

So, what is the difference? Well, everyone believes the wave function is complex, and here I beg to differ. It is, but not entirely. If you recall Euler's theory of complex numbers, you will recall that exp(

iπ) = -1,

i.e. it is real. That means that twice a period, for the very brief instant that

S =

h,

ψ is real and equals the wave amplitude. No need to multiply by complex conjugates then (which by itself is an interesting concept –where did this conjugate come from? Simple squaring does not eliminate the complex nature!) I then assume the wave only affects the particle when the wave is real, when it forces the particle to behave as the wave requires. To this extent, the interpretation is a little like the pilot wave.

If you accept that, and if you accept the interpretation of what the wave function means, then the reason why an electron does not radiate energy and fall into the nucleus becomes apparent, and the Uncertainty Principle and the Exclusion Principle then follow with no further assumptions. I am currently completing a draft of this that I shall self-publish. Why self-publish? That will be the subject of a later blog.