Sheffield ChemSoc's fireworks lecture

A packed out lecture theatre enjoyed a thrilling evening of loud bangs and bright colours as Dr Peter Portius and his research group entertained with their fireworks lecture. Combining fascinating chemistry with vivid displays ensured that it was a thoroughly enjoyable evening for all who attended.

Read on for some amazing photos, and to find out what happened to the gummy bear...

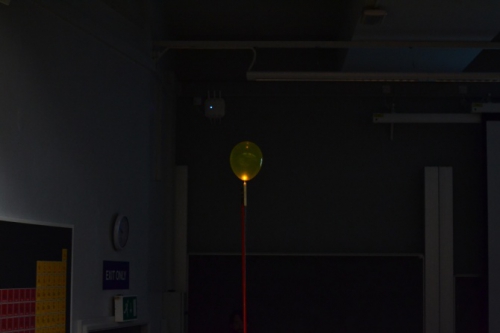

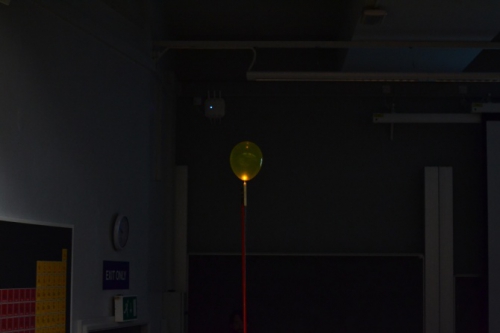

The lecture began with an explanation of the difference between deflagration and detonation. A hydrogen balloon was ignited with a candle causing deflagration. However a balloon containing oxygen and hydrogen detonated when ignited, with a much louder bang.

With the audience’s attention captured, Dr Portius then fixed his sight on an unfortunate gummy bear. To the distress of some in the crowd, the “hell of the gummy bear” demonstrated the high calorific value of the sweet as it was heated with potassium chlorate, a strong oxidizing agent which instantly oxidizes the sugar in the gummy bear, creating a smoke and bright light. Fortunately, the remaining gummy bears were spared.

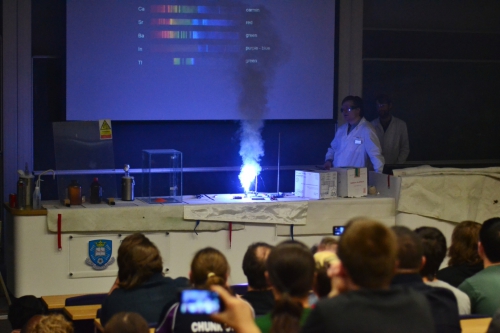

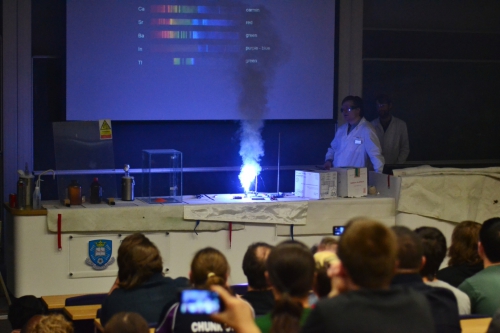

Various metal salts were ignited that burnt intensely with very brightly coloured flames. The colour, and hence wavelength, of the light emitted by the flame is characteristic of the metal present in each example. With the lights turned off, an ammonium dichromate volcano was created by ignition of a pile of the salt with a gas flame, and this burned just like… well, a volcano!

Following the explosions which began the show, a sample of silver azide was heated on a thin metal plate resulting in another loud bang and a deep dent in the plate. Cellulose nitrate was then burnt with an impressive and entirely smokeless flame in the blink of an eye.

It was then demonstrated that combustion does not necessarily require an external heat source, with a paper towel coated in a solution of white phosphorous (P4) in carbon disulfide. Once the carbon disulfide had evaporated, the phosphorus coating the paper spontaneously ignited.

Following this, high energy compounds which were shock-sensitive were demonstrated. Iodine nitride, when flame dried and completely moisture-free, was brushed with a feather giving a purple cloud and a bang.

A valuable lesson for all chemists was learnt in the next demonstration. Starting a fire with magnesium turnings, Dr Portius showed that starving the fire of oxygen with dry ice (solid CO2) is not necessarily the best idea. The fire burned more brightly as the magnesium consumed the carbon dioxide, leaving a chunk of black carbon once the reaction had run its course.

The final two demonstrations were equally impressive. A tightly packed bundle of four cigars dipped in liquid oxygen and ignited burned as brightly as a blow torch, and melting straight through aluminium can. The final experiment was the famous barking dog experiment, notorious for its unreliability. This time the reaction, which demonstrated chemiluminescence, made its characteristic barking sound as the tube was opened and ignited!

About the speaker

Dr. Portius obtained a PhD in Chemistry from Humboldt University in Berlin in 2001, where he worked under the supervision of Prof. AC Filippou on the reactivity of germanium(II) compounds. After his PhD he became a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Nottingham, where he also was a Humboldt Fellow and a Marie Curie Fellow. After a two-year stint as research associate at the University of Bonn he was appointed in 2007 as an EPSRC Advanced Research Fellow at the University of Sheffield, where he is now a lecturer since 2010.

Youtube videos

Oxygen balloon: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mjd_V1_6AFc&feature=share

Lecture theatre time lapse: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Apf1h99PPg

Salts burning with a coloured flame: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UnKib1CR6hg

Barking dog: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I05A3jhL7fs

Acknowledgments

Dr Peter Portius, Ben Peerless, Ben Crozier and Rory Campbell for the immense amount of time and effort that went into creating a thrilling lecture.

Professor Michael D. Ward for photography.

Chris GP Taylor for photography and filming.

Jack Ross for poster designs.

Copyright disclaimer

The copyright holders extend permission for the RSC to use the images for non-profit use only.